Common Rituals During Chinese New Year: Honoring Ancestors and Welcoming Good Fortune

Chinese New Year, also known as the Spring Festival (春节, Chūn Jié), is the most significant traditional celebration for Chinese communities worldwide. Beyond vibrant decorations, reunion feasts, and fireworks, the festival is deeply rooted in rituals and beliefs shaped by centuries of cultural, spiritual, and familial values.

Spanning several weeks rather than a single day, Chinese New Year traditions guide families through a symbolic journey, from purification and preparation to reunion, renewal, and the welcoming of blessings for the year ahead. These practices connect people with ancestors, deities, and communal values, reinforcing continuity, respect, and hope.

Early Preparations: Marking the Start of the Festive Season

Laba Festival (腊八节, Làbā Jié) — 26 January

The Laba Festival, observed on the eighth day of the twelfth lunar month, signals the beginning of Chinese New Year preparations. Traditionally associated with gratitude, harvest celebration, and spiritual reflection, families prepare Laba congee (腊八粥, làbā zhōu), a nourishing porridge made from grains, beans, nuts, and dried fruits. This dish symbolizes abundance, harmony, and warmth, embodying hopes for nourishment and prosperity in the year ahead.

In northern China, another tradition associated with this day is Laba garlic (腊八蒜, làbā suàn), garlic pickled in vinegar that is left to ferment until the Chinese New Year. The vinegar-preserved garlic often turns jade green and develops a sour and slightly spicy flavour, making it a classic accompaniment for jiaozi (dumplings) during the Spring Festival meals. The Chinese word for garlic (蒜, suàn) shares the same pronunciation as “calculate” (算, suàn), echoing the year-end practice of balancing accounts and reflecting on the past year.

Cleaning Out the Old (扫尘, Sǎo Chén)

In the days leading up to Chinese New Year, households perform a thorough cleaning ritual known as “sweeping the dust.” This practice goes beyond physical tidying, it symbolises removing misfortune, negativity, and stagnant energy from the past year to make space for new blessings. The word for “dust” (尘) sounds similar to “old” (陈), reinforcing the idea of clearing away what no longer serves the household before welcoming renewal. Once New Year’s Day arrives, sweeping is traditionally avoided to prevent “sweeping away” good fortune.

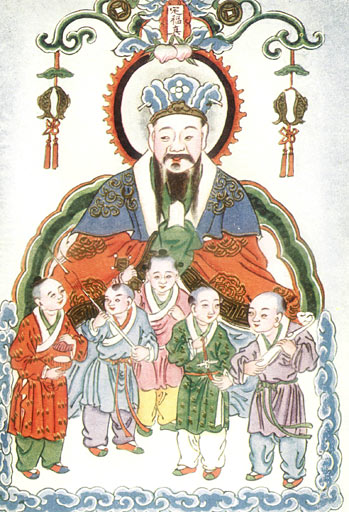

Seeing Out the Kitchen God (祭灶, Jì Zào) — 11 February

A key ritual before the New Year is honouring the Kitchen God (灶神, Zào Shén or 灶君, Zào Jūn), believed to watch over the household throughout the year. According to tradition, he ascends to Heaven shortly before Chinese New Year to report the family’s conduct to the Jade Emperor. Families make offerings of incense, sweets, honey, or sticky treats to “sweeten” his mouth, symbolically ensuring a favourable report. After the ritual, the Kitchen God’s image may be burned or replaced, marking his departure and eventual return in the new year with renewed blessings. This observance, often associated with Little New Year (小年, Xiǎo Nián), also signals the transition from preparation to celebration.

Ancestral Worship: Remembering Family Roots (祭祖, Jì Zǔ)

One of the most meaningful rituals during Chinese New Year is ancestral worship, typically performed on New Year’s Eve or New Year’s Day. Families set up altars at home, display ancestral tablets or photographs of deceased relatives, and offer cooked dishes, fruits, tea, sweets, and incense to invite ancestors to symbolically “join” the family celebrations. Lighting incense and bowing expresses filial piety, gratitude, and respect. Many families also burn joss paper (spirit money), symbolising the sending of comfort and wealth to ancestors in the afterlife. This ritual reinforces family continuity across generations while seeking ancestral blessings for peace, health, and prosperity in the year ahead.

Chinese New Year’s Eve (除夕, Chúxī) — 16 February

Chinese New Year’s Eve is the emotional and spiritual heart of the festival. Families gather for the reunion dinner (年夜饭, nián yè fàn), a symbolic feast centred on unity and abundance. Dishes often carry auspicious meanings such as fish for surplus, dumplings for wealth, and long noodles for longevity. Many families observe “staying up to welcome the year” (守岁, shǒu suì), believing it brings longevity and protection. Homes are brightly lit, ancestors are honoured, and prayers or firecrackers are used to usher out the old year.

New Year’s Day / Spring Festival (大年初一, Chū Yī) — 17 February

The first day of Chinese New Year focuses on auspicious beginnings. People wear new clothes, exchange well wishes, and greet relatives with phrases of prosperity and health. Red envelopes (红包, hóngbāo) are given by elders to younger family members as symbols of blessing and protection. Traditional taboos include avoiding sweeping, washing, or breaking items, as these actions are believed to bring bad luck. The emphasis is on positivity, harmony, and starting the year on the right note.

Temple Visits: Praying for Luck and Protection

Visiting temples during Chinese New Year is common among Buddhist, Taoist, and folk believers. Devotees burn incense, offer prayers, and seek blessings for health, wealth, and protection. Common practices include praying to deities such as the God of Wealth (财神, Cái Shén) or Guanyin (观音), and performing the “first joss stick” ritual (头香, tóu xiāng) after midnight to attract early blessings. Temples are lively in the first few days of the New Year, blending spiritual devotion with festive energy.

Significant Days During the New Year

Day 2 (大年初二, Chū Èr) — Traditionally, married daughters return to their parental homes with their spouses to pay respects and continue celebrations, symbolising family balance and reunion.

Day 6 (大年初六, Chū Liù) — Associated with sending away the Ghost of Poverty, this day marks a return to activity. Families resume cleaning, discard old items, and symbolically release lingering misfortune to welcome smoother fortunes ahead.

Day 7 — Everyone’s Birthday (人日, Rén Rì) — Known as the “Birthday of Humankind,” this day celebrates the creation of humans. Special foods such as seven-vegetable dishes or noodles are eaten to wish for health and longevity.

Lantern Festival (元宵节, Yuánxiāo Jié) — Day 15 — The Chinese New Year period concludes with the Lantern Festival, celebrated under the first full moon of the lunar year. Families admire lantern displays, solve riddles, and eat tangyuan (汤圆) — glutinous rice balls symbolising unity and completeness. This final celebration marks the transition from festivity back to everyday life, carrying hopes of harmony and fulfilment into the months ahead.

Conclusion

Chinese New Year traditions are rich in symbolism and meaning, rooted in the values of family, gratitude, renewal, and hope. From the Laba Festival’s steaming bowls of congee and emerald-green Laba garlic, through ancestral worship and family reunions, to temple prayers and lantern festivals, each ritual helps weave a tapestry of cultural heritage that connects past and present, home and community. Together, these customs create a festive calendar that celebrates continuity while welcoming new beginnings, making the Spring Festival a deeply meaningful and joyous season for communities around the world.